The Starr Years: 1948-1978

There is one timeless way of building… It is a process through which the order of a building grows directly from the inner nature of the people, and the animals, and plants, and matter which are in it.”

-Christopher Alexander, The Timeless Way of Building

The Alexander property was sold in 1948 to Merritt Paul Starr and Harriet Case Starr, who were living in Medina at the time, while Merritt was serving his residency at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle. Of the couple, Merritt was likely the one who was drawn to the rural setting of Mercer Island. Although recently accessible by the world’s longest floating bridge, Mercer Island still remained a secluded, rural community attracting residents of a more vigorous and adventurous spirit. Merritt’s nature fit perfectly with the life of the rugged individualist and someone who wanted to live close to the land. In interesting ways the Mercer Island property must have beckoned to him just as it did to David Alexander some 45 years earlier. Harriet by contrast, had lived a more refined and sheltered life, and she saw in Merritt a vigorous spirit who would help her find further expression for her unfolding potentials.

Both Merritt and Harriet descended from prominent families whose involvement in the formation of the United States was well documented even before the American Revolution. Merritt was a direct descendant of Dr. Comfort Starr, a young surgeon and educator who arrived to America in 1635 and who quickly became active in the formation of the new nation. Dr. Starr was one of the six original founders of Harvard, and it was his home that held the first classes of the new University. Later the home and property were to be the beginning of the Harvard campus, around which the school grew. Latter generations of Starrs were filled with noted educators, lawyers and physicians. Merritt’s grandfather, a prominent Chicago lawyer, was an acquaintance of Teddy Roosevelt, and Merritt’s father Dr. Merritt Starr, a Lieutenant Colonel in the Army Medical Corp, later served as the Dean of the USC Medical School. Merritt’s uncle, Phillip Comfort Starr, was a young, promising university professor who lost his life in Ypres, France in WWI while serving with a Canadian Artillery Unit. Uncle Phil was an adventurous spirit, and a man who would have great influence upon the young Merritt.

Harriet was a descendant of the Dexter family, as noted as the Starr family in early American history. John Dexter was a graduate of Harvard and a church deacon in the town of Malden, Massachusetts. George Washington took lodging at the Dexter home on numerous occasions, and on one visit in 1775, accidently dislodged a stone from a wall outside the Dexter house. Told that a servant would replace the stone, Washington protested, saying he preferred to leave things as he found them, and replaced the stone himself. Another noted Dexter was Samuel, who served as Secretary of War under John Adams in 1801. Harriet grew up in a stable, nurturing family in Wilmette, Illinois. Her father was a partner in the prominent Chicago investment firm of Bosch and Case, and his success included a comfortable home on the shore of Lake Michigan, which was Harriet’s childhood home. Harriet’s mother passed away at a young age, which left her an only child in the care of her grandparents, Dexter and Harriet Donelson. The Donelson’s brought Harriet to San Marino, an affluent small village adjoining the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, California in the early 1930’s. Around the corner from their home lived a curious man who spent time at the school, working out the details of his Theory of Relativity. Harriet would often see Dr. Einstein walking his dog past her house. The young Harriet was inspired by the life of her great aunt, Katharine Dexter McCormick, a Chicago suffragette, philanthropist and biologist, who became the second woman to graduate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the first with a science degree in biology. Heir to the McCormick fortune, Katharine not only used her resources to fund the development of the first birth control pill, she helped oversee the laboratories and participated in the research.

Merritt and Harriet met at the North Shore Country Day School, a private college prep school located in Winnetka, Illinois near both the Starr and Case Family homes. Merritt and Harriet were in a chamber music group together, Harriet playing the piano and Merritt the cello. At age 16 Merritt joined some friends on a road trip to Taos, New Mexico, where they rode horseback to Blue Lake, considered the sacred birthplace of the Taos Indian nation. While there Merritt contacted Rheumatic fever and suffered serious heart damage. Harriet always believed that this occurred because the boys had violated the sacred Taos grounds, which in 1936, were the center of a contentious ownership battle between the Taos nation and the Federal Government. After high school Merritt attended Oberlin, the liberal arts college renowned not just in the sciences, but also for having the oldest Music Conservatory in America. Although Merritt would eventually become a physician, he really wanted to be a musician, and Oberlin was likely the place where Merritt resolved the path of his future vocation. Harriet attended Bryn Mawr College, a prestigious, highly selective liberal arts college for women, noted as the first American University to offer graduate degrees to women. Harriet was drawn to the quality of the school and the rigorous intellectual challenge that Bryn Mawr offered.

After completing college Harriet and Merritt married, and were soon expecting their first child Katharine. Merritt finished up medical school at Northwestern University, and then headed to Seattle to begin his residency at Harborview. Living in Medina, the Starrs were expecting their second child Sarah, and began looking for a home for the growing family. In 1948 or 1949, they found the Alexander Estate on Mercer Island for sale, purchased the five acres and immediately began plans to build a new home, remarkable for a young couple of 26 and 28 years old.

Merritt had a close childhood friend from Chicago, Marshall Forrest, who had recently moved to Bellingham to begin a career in law. Forrest served Washington as a State Representative, a member of the Board of Trustees at Washington State University and later, as a Washington State Court of Appeals Judge. In 1949, Forrest hired noted Seattle architect Fred Bassetti to design his home in Bellingham. Bassetti’s architectural firm was at the same time designing two noted Elementary Schools on Mercer Island, Lakeview and Lakeridge. The Marshall Forrest house was an innovative design, winning acclaim immediately and remained one of Bassetti’s favorite designs. Merritt Starr was in contact with Forrest while the design evolved, and seeking his own architect for his Mercer Island home, likely received the referral of an architect through Marshall’s connection with Bassetti. The name of the architect who designed the Starr home has yet to be found.

The Starr house, completed in 1950, was a charming rambler with an open U-shape that formed a courtyard toward the swimming pool to the north. The pool was in fact the wine cellar of David Alexander’s old home, reclaimed. The house featured hand-split cedar siding, a shake roof, and heated concrete floors smoothed to a glossy waxed finish. The Starrs, appreciating the orchards, gardens and outbuildings left by Alexander, removed only what was necessary to build the new house, and over time added more fruit trees. The home’s design drew favorable attention, and in the early 1950’s was featured in Better Homes and Gardens Magazine.

Harriet embraced the rural life-style, feeling liberated from her sheltered, groomed childhood, and she extended that sense of freedom to her two daughters. The Starr home quickly evolved into a full-fledged farm, with Harriet in the midst of it. She raised all the animals, which in time included three horses, countless chickens, ducks, a rabbit, dogs and cats. Their first cow, Jill, would frequently wander into the Living Room when she was bored, and stare at herself in the window’s refection. This was eventually remedied with the acquisition of Jack, after which Jill found other things to do. Harriet also pressed apples from the orchard, did pottery, maintained the gardens, and made forty-proof Applejack with neighbor Jack Hurney, a Boeing test pilot, and his wife Jerry. The Starr daughters, banding with other girls not yet 10 years old, donned themselves “The Vigilantes” and explored Mercer Island on horseback, limited only by the shores of Lake Washington.

Merritt meanwhile had finished his residency, and in 1951 took a job in Alaska, traveling back and forth to Seattle regularly. It is possible that Merritt’s adventurous spirit slowly pulled him away from his family toward the frontiers of Alaska, but is equally possible that Merritt was influenced by his serious medical condition, which as a physician, he would have known was deadly. In 1955, he suffered his first heart attack at age thirty-five, and his condition only worsened. Ten years earlier, his father, still a physician in the Army medical Corp, would publish the research paper “Physical Reconditioning after Rheumatic Fever” that appeared in JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association, undoubtedly the work of not only a distinguished doctor, but of a concerned father. Merritt may have believed his life could be short, so he filled it with a passion. Merritt quickly began spending increasing time in Alaska, playing cello with the Anchorage Symphony Orchestra, writing a piano concerto, and helping to build a hospital in Matzatlan.

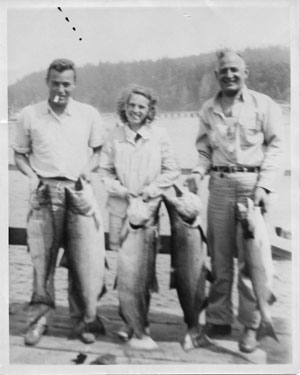

In time it was clear that Merritt was pursuing a separate life, and the Starrs divorced. But Merritt did not disappear into the wilds of Alaska, instead he continued to leave his mark in the world. He established a home and medical practice in Anchorage, and later built a cabin on Lost Lake, where he could hunt and fish to his heart’s desire. His motorboat was kept in Seward, on the ready for when the salmon ran, and after obtaining a pilots license, he purchased a single seat Aeronca 7DC, and later flew a Cessna 150. Merritt always carried his black doctor’s bag with him, treating as many patients on the road as he did from his Anchorage office. “Doc” Merritt also involved himself in politics, most notably the effort to relocate the State Capitol from Juneau. He also was a member of the Alaska World Affairs Council, and met JFK when he spoke at the Council during the 1960 Presidential campaign. Eventually Merritt would marry a wonderful woman named Helen, and they would build a new home together, renting out the lower floor of the house to Alaska Airline pilots and stewardesses. The Rheumatic Fever finally took its toll on Merritt, ending his life in 1969 at the young age of 49. Merritt knew his time was precious, and he filled every moment of his life with the joy of the outdoors and his desire to help others. In the last years of his life, Merritt had received a $50,000 research grant from the Atomic Energy Commission to develop a cancer diagnostic tool using barium, but he did not live to see the research through.

In 1952 Harriet, still raising her daughters on the Mercer Island estate, entered the University of Washington to study Psychology with the goal of earning a PhD. While at the UW, she met William Sumerwell, a biochemist who was researching bound ascorbic acid and later amalyse. They married, and Bill moved into the Starr home with his daughter. In 1956 they added a Master Bedroom with a fireplace for themselves, and a bedroom between the detached garage and the east end of the house for one of the daughters. In 1960 the Sumerwells moved to Washington DC, in part from Bill’s disillusionment with his research, which he believed had been attributed to others at UW, who later received a Nobel Prize in Physiology based in part upon Sumerwell’s contributions. Harriet, feeling a strong attachment to the Mercer Island home, retained ownership and instead rented it to a group of pilots, who in the 1970’s found the secluded estate perfect for hosting wild parties around the outdoor pool.

In Washington, DC, Harriet pursued the completion of her Masters degree, which she obtained from American University in 1977. She worked as a Mental Health Counselor, and later became certified as a gemologist, operating her jewelry business ”Jacaranda” from her home. Her marriage to Bill Sumerwell thrived for forty years, giving them four more children in addition to the three they shared from their prior marriages. Like Merritt Starr, Bill Sumerwell loved music, the clarinet being his chosen instrument. Also like Merritt, Bill suffered from Rheumatic fever contracted as a child, and died from a sudden heart attack in 1992. Both Bill and Harriet, she passed away in 2011, gave generously to the Arts and Music in Washington DC, as well as organizations promoting mental health and civil rights.

In 1978 Harriet finally gave up the home on Mercer Island, but never stopped cherishing it and the fond memories it provided. The buyer, William F. Wuerch, planned to immediately sub-divide and develop the property. At that moment, it appeared that the dreams, nurturance and hard work provided by both the Starrs and the Alexanders were all about to come to a tragic end, an ending that would have been deeply painful for Harriet.